The fourteenth child of the immensely wealthy Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork, Robert Boyle inherited land and property in England and Ireland which yielded a substantial income. He never had to work for a living, and following three years of travel and study as a teenager in Europe, Boyle decided at the age of 17 to devote his life to scientific research and the cultivation of what was called the “new philosophy”.

In Britain, Boyle was the leading figure in a move away from the Aristotelian view that knowledge was best obtained by the use of reason and logic. Boyle rejected this argument, and insisted that the path to knowledge was through empiricism and experiment. He won over many to his view, notably Isaac Newton, and in 1660 Boyle was a founding member of a society which believed that knowledge should be based first on experiment; we know it today as the Royal Society.

Boyle carried out a wealth of experiments in many areas of physics and chemistry, yet he seems to have been content with obtaining experimental results and generally stopped short of formulating theories to explain them.

Leibniz expressed astonishment that Boyle “who has so many fine experiments, had not come to some theory of chemistry after meditating so long on them”.

But what about Boyle’s law? you ask.

Well, it may surprise you to know that Robert Boyle did not originate the pressure-volume law commonly called Boyle’s law. A description of the reciprocal relation between the volume of air and its pressure does first appear in a book written by Boyle, but he refers to it as “Mr Towneley’s hypothesis”, for reasons we shall see.

– – – –

Torricelli leads the way

It was Evangelista Torricelli (1608-1647) in Italy who started it all in the summer of 1644 with the invention of the mercury barometer. It was an impressive device, made all the more impressive by the insight that came with it. For one thing, Torricelli had no problem accepting the space above the mercury as a vacuum, in contrast to the vacuum-denying views of Aristotle and Descartes. For another, he was the first to appreciate the fact that air had weight, and to understand that the column of mercury was supported by the pressure of the atmosphere. As he put it: “We live submerged at the bottom of an ocean of air, which by unquestioned experiments is known to have weight.”

This led Torricelli to surmise that atmospheric pressure should be less in elevated places like mountains, an idea which was put to the test in France by Blaise Pascal, or more precisely by Pascal’s brother-in-law Florin Périer, who happened to live in Clermont-Ferrand, which has Puy de Dôme nearby.

On Saturday, September 19, 1648, Florin Périer and some friends performed the Torricelli experiment on the top of Puy de Dôme in south-central France. The height of the mercury column was substantially less – 85 mm less – than the control instrument stationed at the base of the mountain 1,400 metres below.

The Puy de Dôme experiment provided Pascal with convincing evidence that it was the weight of air, and thus atmospheric pressure, that balanced the weight of the mercury column. Torricelli’s instrument provided a convenient means of measuring this pressure. It was a barometer. The news quickly spread to England.

– – – –

Reaching new heights

The Torricellian experiment was demonstrated and discussed at the scientific centres of learning in London, Oxford and Cambridge from 1648 onwards. At Cambridge, there was an enthusiastic experimental scientist by the name of Henry Power, who was studying for a degree in medicine at Christ’s College. Power’s home was at Halifax in Yorkshire, and this gave him the opportunity to verify the Puy de Dôme experiment because unlike London, Oxford and Cambridge, the land around Halifax rises to significant heights.

On Tuesday, May 6, 1653, Henry Power carried the Torricellian experiment to the summit of Halifax Hill, to the east of the town, where he was able to verify Pascal’s observation. In further experiments, he began to investigate the elasticity of air – i.e. its expansion and compression characteristics. And it was this change of focus that was to characterise England’s contribution to the scientific study of air.

The pioneering work in Italy and France had been concerned with the physical properties of the atmosphere. In England, attention was turning to the physical properties of air itself.

– – – –

The Spring of the Air

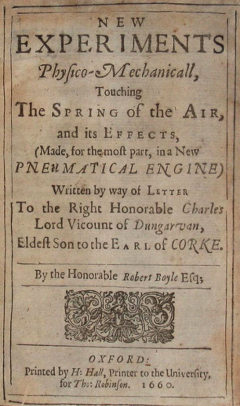

In 1654, the year after Henry Power’s excursion on Halifax Hill, Robert Boyle arrived in Oxford where he rented rooms to pursue his scientific studies. With the assistance of Robert Hooke, he constructed an air pump in 1659 and began a series of experiments on the properties of air. An account of this work was published in 1660 under the title “New Experiments Physico-Mechanicall, Touching The Spring of the Air, and its Effects”.

Boyle’s book was a landmark work, in which were reported the first controlled experiments on the effects of reduced air pressure. The experiments are divided into seven groups, the first of which concern “the spring of the air” i.e. the pressure exerted by the air when its volume is changed. It is clear that Boyle had an interest not only in demonstrating the elastic nature of air, but also in finding a quantitative expression of its elasticity. Due to inefficiencies in the air pump and the inherent difficulties of the experiment, Boyle failed in his first attempt. But it was not for want of trying.

– – – –

Enter Mr Towneley

Richard Towneley, whose home was near Burnley in Lancashire, northern England, was curiously similar to Robert Boyle in that the Towneley family estate also generated an income which meant that Richard did not have to work for a living. And just like Boyle, Towneley devoted his time to scientific studies.

Now it just so happened that the previously-mentioned Henry Power of Halifax was the Towneley family’s physician. This gave Richard and Henry regular opportunities to share their enthusiasm for scientific experiments and discuss the latest scientific news.

In 1660 they both read Robert Boyle’s New Experiments Physico-Mechanicall, and this prompted further interest in the study of air pressure which Power had conducted on Halifax Hill seven years earlier. Not far to the north of Towneley Hall is Pendle Hill, whose summit is 1,827 feet (557 meters) above sea level, and it was here that Power and Towneley conducted an experiment that made history.

On Wednesday 27th April 1661, they introduced a quantity of air above the mercury in a Torricellian tube. They measured its volume, and then using the tube as a barometer, they measured the air pressure. They then ascended Pendle Hill and at the summit repeated the measurements of volume and air pressure. As expected, there was an increase in volume and a decrease in pressure.

Although their measurements were only roughly accurate and doubtless affected by temperature differences between the base and summit of the hill, the numerical data was sufficient to give them the intuitive realization of a reciprocal relationship between the pressure and volume of air

On a high hill in northern England, nature revealed one of its secrets to Henry Power and Richard Towneley. Now they needed to communicate their finding.

– – – –

Boyle reports the news

It was not until two years after the Pendle Hill experiment that Henry Power eventually got around to publishing the results in Experimental Philosophy (1663). This delay explains why history has never associated the names of Power and Towneley with the gas law they discovered, because the news from Pendle Hill was first given to, and first reported by, Robert Boyle.

In the appendix to the second edition of his New Experiments Physico-Mechanical published in 1662, Boyle reports Power and Towneley’s experimental activities, which in error he ascribes solely to Richard Towneley. It was on the basis of this second edition of Boyle’s book that the reciprocal relationship between the volume of air and its pressure became known as “Mr. Towneley’s hypothesis” by contemporary authors such as Robert Hooke and Isaac Newton.

A complication was added by the fact that Power and Towneley’s experiment led Boyle to the idea of compressing air in a J-shaped tube by pouring mercury into the long arm and measuring the volume and applied pressure.

From this experiment, conducted in September 1661, Boyle discovered that the volume of air was halved when the pressure was doubled. Curiously, he translated this finding into the hypothesis that there was a direct proportionality between the density of air and the applied pressure.

It didn’t occur to Boyle that the direct relation between density and pressure was the same thing as the reciprocal relation between volume and pressure discovered earlier by Power and Towneley. Boyle seems to have thought that compression was somehow different to expansion, and that his experiment broke new ground.

For this reason Boyle believed he had discovered something new, and since his name was far better known in scientific circles than that of Henry Power and Richard Towneley, it was inevitable that Boyle’s name would be associated with the newly-published hypothesis, which in time became Boyle’s law.

– – – –

Postscript : La loi de Mariotte

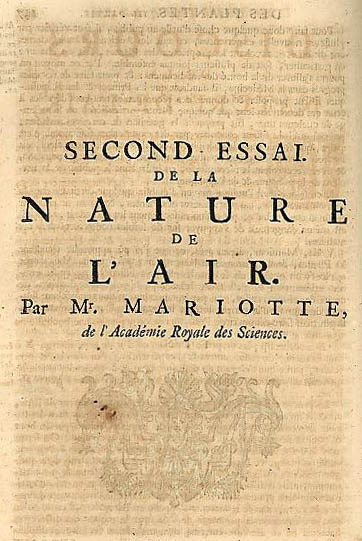

The pressure-volume law discovered by Power and Towneley, and confirmed by Boyle, is known as Boyle’s law only in Britain, America, Australia, the West Indies and other parts of what was once called the British Empire. Elsewhere it is called Mariotte’s law, after the French physicist Edme Mariotte.

Mariotte stated the pressure-volume relationship in his book De la nature de l’air, published in 1679, some 17 years after the second edition of Boyle’s New Experiments Physico-Mechanical. Mariotte made no claim of originality, nor did he make any reference to Boyle. But he was an effective publicist for the law, with the result that his name became widely associated with it.

Some might argue that the attribution is not quite deserved. However, Edme Mariotte stated something immensely important that Robert Boyle neglected to mention. He pointed out that temperature must be held constant for the pressure-volume relationship to hold:

In the view of CarnotCycle, the pressure-volume law so stated can with justification be called Mariotte’s law.

– – – –

P Mander January 2016

Thank you for the input, it adds another dimension to the story. I wish I knew more about Towneley and his circle; the significant contribution they made to the development of the ideal gas law is not widely recognized and more should be written about them.

LikeLike

Another reason why Richard Towneley could engage in scientific research (apart from a passion for it) was that he was a Catholic, and therefore could not join any of the professions or take part in the administration of the country. He had to find an outlet for his considerable intelligence. He and his friends were also recognisably besotted with the scientific equipment, and kept on inviting each other round to play with their latest acquisitions.

LikeLike

I usually name this law : “loi de Boyle-Mariotte” in French, but I didn’t heard anything about Power and Towneley, thanks.

LikeLike

Some comments:

1. Torricelli has the hairiest lab coat I have ever seen (:

2. I would dig having that much mercury to experiment with, but then again would be too frightened of it to do anything with it.

3. “Elasticity” of air was once used to describe its suitability for breathing. Old works describe the danger of air that had “lost its elasticity” in caves, wells, etc.

4 and last. I love your expositions of hard science history.

LikeLike